Understanding what spiritual emergence and spiritual emergency are, how they differ from psychosis, and how to integrate them as a psychedelic traveler or practitioner.

This is part of our ongoing series on transpersonal psychology and how it can help us understand psychedelic experiences. Check out part 1, ‘What is Transpersonal Psychology?’ here.

In recent years there has been a resurgence of interest in the therapeutic potentials of psychedelic substances within both clinical and non-clinical settings, with many seeking out psychedelics and plant medicines for spiritual purposes and attempts at self-healing. Psychedelics have the ability to catalyze immense shifts in our understanding and perceptions of reality as well as the potential to bring forth that which is latent within the psyche. Although the sudden eruption of psychic content or change in ways of seeing the world is at the core of psychedelic healing, it can be a destabilizing process that occasionally triggers a type of unintended psychological distress known as “spiritual emergency.”

What Is Spiritual Emergency?

The term “spiritual emergency” was introduced to the field of transpersonal psychology by psychiatrist Stanislav Grof and his late wife, psychotherapist Christina Grof, in the 1980s to refer to a kind of spiritual or transformative crisis in which an individual could move towards a greater state of integration and wholeness. In their groundbreaking book on the subject, Spiritual Emergency: When Personal Transformation Becomes a Crisis, the Grofs describe spiritual emergency as “both a crisis and an opportunity of rising to a new level of awareness.”

Intentionally constructed as a play on words, the term “emergency” indicates crisis, all the while containing within it the term “emergence”, pertaining to the process by which something becomes known or visible, implying that both—crisis and opportunity—can arise. The Grofs thus differentiate between a spiritual emergency and the more gradual, less disruptive process of spiritual emergence.

Compared with spiritual emergency, the process of spiritual emergence, sometimes referred to as ‘spiritual awakening’, consists of a slower, gentler unfoldment of psychospiritual energies that does not negatively affect an individual’s ability to function within the various domains of their life. Thus, spiritual emergence is a natural process of attuning to a more expanded state of awareness in which individuals generally feel a deeper sense of connection to themselves, others, and the world around them.

Conversely, cases of spiritual emergency usually share many characteristics with psychosis, and as such are often misunderstood and misdiagnosed. However, spiritual emergencies differ from psychosis in that they are not suggestive of long-term mental illness, and provide individuals with an opportunity to use their woundedness to go deeper into themselves and find healing.

The fact that the concept of spiritual emergency is not known and widely accepted beyond the context of transpersonal psychology is partially bound up with an age-old argument that has long permeated Western science and culture. In culture at large, spiritual and mystical-type experiences have long been ridiculed and pathologized, being considered delusional and reflective of mental illness. Dominated by materialist approaches to consciousness and mental health, Western science generally lumps spiritual crises together with psychosis, attributing their origins to biological or neurological dysfunction and treating them on the physical level. However, in the context of transpersonal psychology, spiritual experiences are considered to be real and integral to the evolutionary development of the individual.

Inherent to the Grofs’ concept of spiritual emergency is their holotropic model that revolves around the central tenet that we have an innate tendency to move towards wholeness, possessing within us an “inner healing intelligence.” Similar to the way the body starts its own sophisticated process of healing when we injure ourselves physically, the psyche possesses its own healing intelligence that takes place unseen within us. Just like fevers fighting off infections, spiritual crises can be understood as the psyche’s way of signalling that imbalance needs to be overcome as it moves toward a state of greater integration.

Although experiences of spiritual emergency are highly individual, they all share in the fact that the typical functioning of the ego is impaired, and the logical mind is overridden by the world of intuition. Scary and potentially traumatizing, spiritual emergencies can be interspersed with moments of fervent ecstasy in which an individual believes that they have special abilities to communicate with God or cosmic consciousness, giving way to a temporary messianic complex.

Conversely, a person might become possessed by a potent feeling of paranoia, feeling that the universe is conspiring against them, or they may feel detached from material reality, only connected to this realm through a fine, ephemeral thread. Happenings and material objects might become imbued with symbolic, other-worldly meaning. For some it means spirit possession, compulsive behaviors which lead them to forget to eat and sleep, or a soul-crushing sense of depression that makes them choose to isolate themselves from others.

Spiritual Emergency Triggered By Psychedelics

Although states of spiritual crisis can come about spontaneously, they can be triggered by emotional stress, physical exertion, disease, near-death experiences, childbirth, meditative practice, and exposure to psychedelics, among other things.

Psychedelics, in particular, have the ability to trigger spiritual emergencies in that they rapidly propel a journeyer from one state of consciousness to another in a mere matter of hours. If an individual is not adequately prepared, these sudden encounters with the numinous can be incredibly destabilizing and have challenging, unintended impacts.

Furthermore, psychedelics can activate parts of the psyche, throwing us off balance by rapidly bringing forth material from the unconscious that we need to integrate. The Grofs expand on this further in their book, Stormy Search for the Self: A Guide to Personal Growth through Transformational Crisis, writing, “Occasionally, the amount of unconscious material that emerges from deep levels of the psyche can be so enormous that the person involved can have difficulty functioning in everyday reality.”

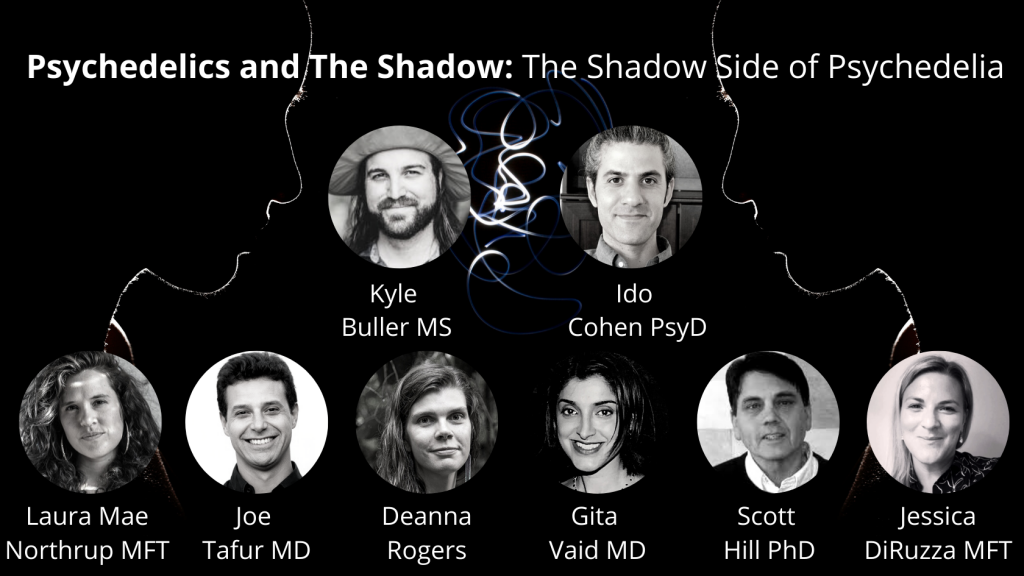

According to Kyle Buller, Co-Founder and Director of Education here at Psychedelics Today, M.S. in Clinical Mental Health, and certified Spiritual Emergence Coach, psychedelics and engaging in spiritual and contemplative practices can make individuals more prone to spiritual emergencies. “Psychedelics and plant medicines open us up to new ways of seeing the world, and this new way of being or seeing can be destabilizing for some,” he says.

Additionally, Buller explains that those with existing traumas or underlying mental health disorders are more at risk for spiritual emergency-type experiences. “I come back to Grof’s notion that psychedelics are ‘non-specific amplifiers of mental or psychic processes,’” he explains. “If someone is already dealing with a lot and difficult content is brought to the surface and amplified, they might not be able to contain it without a proper set and setting or support.”

In the context of psychedelics, spiritual crises can occur when there is an expansion of consciousness that happens without adequate containment. For that reason, most spiritual emergencies triggered by psychedelics don’t occur in the context of clinical studies, but rather through recreational use, self-exploration, and even ceremonial use. Arguably, within plant medicine ceremonies, there are clear parameters that contain the experience as it is unfolding, however, upon leaving the container of the ceremony, most individuals go back to their normal, everyday lives, and this shift can be challenging.

Research fellow at the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary University of London, Jules Evans, detailed his experience of a psychedelic-induced spiritual emergency in his self-published, Holiday From the Self: An Accidental Ayahuasca Adventure. In Evans’ case, he went to the Peruvian Amazon to participate in an ayahuasca retreat.

Although Evans gave it careful consideration and had a positive experience at the retreat, once he began travelling back to Iquitos, he found himself feeling disconnected, and moreover disorientated. As the days passed by, an eerie and intense feeling of doubt around his sense of reality washed over him. In an article recounting his experience he writes, “When I got texts from loved ones, I thought my subconscious was constructing them. I felt profoundly alone in this fake reality.”

Evans had previously spent time studying ecstatic experiences academically, and was partially familiar with the concept of spiritual emergency, helping him to not “freak out.” However, for most of us, that isn’t the case and when spiritual crises start to unfold, not knowing what is happening can plunge us into a deep state of fear and terror.

Another reason why those who experiment with psychedelics are more prone to spiritual crises is the lack of cultural support. Buller places emphasis on the need for adequate cultural containers, suggesting that the fact that psychedelics and plant medicines are not accepted by dominant culture poses another hurdle for integrating these experiences.

“When a person has a profound experience, where do they turn or seek support? Does the cultural cosmology around them embrace these types of experiences and if not, how does that exacerbate one’s difficult experience?” Buller says.

In Western culture, we have lost the cultural frames and mythological maps that could usher us through intense experiences of psychospiritual opening, a process which we need to go through at times. Reflecting on this subject in a 2008 paper, medical anthropologist Sara Lewis, explored how Westerners are at increased risk for experiencing spiritual crises and psychological distress following ayahuasca ceremonies due to what she describes as a “lack of cultural support.”

Spiritual crises have been suggested to resemble instances of ‘shamanic illness’ as experienced by shamanic initiates in certain Indigenous cultures. Compared with those in Indigenous communities, however, Westerners lack community resources and guidance to contextualize experiences produced by psychedelic plant medicines, and often fear becoming mentally ill as a result.

Distinguishing Between Psychosis and Spiritual Emergency

The Grofs suggest in their book, Spiritual Emergency, that mainstream psychiatry and psychology make no distinction between mystical states and mental illness, tending to treat non-ordinary states with suppressive medication rather than recognizing their healing potentials.

For psychedelic practitioners and integration providers working with those experiencing psychological distress after a psychedelic experience, evaluating whether the individual is a danger to themselves and others, and determining personal or family history of mental health disorders can be incredibly helpful in understanding whether the phenomenon is a psychotic break or a spiritual crisis. An additional indicator is understanding how a given individual relates to their spirituality, ascertaining whether it brings them a sense of hope. Further, it is useful to rule out any form of neurologic or physical disorder that would impair normal mental functioning such as an infection, tumor, or uremia.

Another crucial factor is the client’s ability to understand the phenomenon as an unfolding psychological process that they can navigate internally as well as cooperatively with the mental health provider, being able to differentiate to a substantial degree between their internal experience and consensus reality.

In a 1986 paper on the subject, the Grofs caution, “It is important to emphasize that not every experience of unusual states of consciousness and intense perceptual, emotional, cognitive, and psychosomatic changes falls into the category of spiritual emergency.” Further highlighting that the concept of spiritual crisis is not intended to counter traditional psychiatry, but rather offer an alternative to those who are able to benefit from it.

Thus mental health practitioners looking to learn how to distinguish between spiritual emergency and psychosis must learn there is a fine line between the two which often makes it difficult to discern. While there is a tendency for traditional psychiatry to pathologize mystical states, the Grofs jointly warn of the dangers of “spiritualizing psychotic states”, placing emphasis on the need to use proper discernment around a given individual’s experience.

Speaking to the subject, Buller offers advice, “I would encourage a combination of open-mindedness and critical thinking. For many mental health professionals, this concept is going to push against most of our training, however, we need an open mind to explore this area and do our best to listen to the experiencer.”

How to Deal with a Spiritual Crisis

In a culture where spiritual issues are not easily understood, spiritual crises can be incredibly isolating and shameful in that the person undergoing them feels that they cannot open up and share about their experience with others for fear of being labeled as “crazy.”

Reflecting on people’s reluctance to share about these types of challenges, Buller offers, “I think this highlights some distrust in the current system around these types of experiences.” He adds, “It also makes me wonder how many people may be struggling with difficult experiences and aren’t reaching out for help because of fearing what might happen if they disclose their experience to a mental health professional.”

For those undergoing a spiritual emergency, it can feel comforting to know that they are not alone in their struggle, and that many other people have been through similarly challenging experiences. It is also helpful to remember that the crisis is part of the healing process, and that it too will pass.

One resource is the Spiritual Emergence Network (SEN), founded by Christina Grof in 1980, or its global sister project, the International Spiritual Emergence Network (ISEN) which provides practical advice for navigating spiritual emergency as well as offering a specialized mental health referral and support service for those seeking help. Additionally, for those merely looking to learn more about the subject, Psychedelics Today offers a free webinar called, “Spiritual Emergence or Psychosis,” which explores some of the research around psychosis and spiritual emergence.

When experiencing a spiritual emergency as a result of psychedelic use, it is important to factor in set, setting, and integration, just as one would factor those components into an intentional psychedelic trip in the first place. In terms of ‘setting,’ the person experiencing the spiritual crisis should seek out a non-judgemental space in which they feel safe and supported—whether that be with a mental health practitioner or in the hands of family and friends.

Beyond the environment, ‘set’ refers to our mindset and the way we frame the experience. Because there is a conceivable amount of stigma surrounding spirituality, cultivating one’s mindset means understanding that there is nothing ‘wrong’ with the person experiencing a spiritual emergency, and that the difficulty may very well be a crucial stepping stone on their personal path to healing.

Lastly, meaning-making in the context of psychedelic integration is of paramount importance as it allows individuals to take the crucial step of transforming negative experiences into something of value, which could take anywhere from a couple of months to the rest of their lives.

When working with someone experiencing a spiritual emergency, it is important to take a destigmatizing and non-pathologizing approach. Recognizing this, Stanley Krippner, psychologist and parapsychologist, wrote in a 2012 paper, “The naming process is one of the most important components of healing.” As such, mental health practitioners working with those experiencing psychological distress after a psychedelic experience need to be mindful in how they frame what is happening.

Spiritual Emergency Beyond the Scope of Transpersonal Psychology

While the Grofs’ concept of spiritual emergency was undoubtedly ahead of its time, there is still room for growth and maturation, and some suggest it may be helpful to use different terminology around the concept.

David Lukoff, professor of psychology at Sofia University and licensed psychologist specializing in the treatment of religious and spiritual crises, was influenced by the Grofs’ concept of spiritual emergency early on in his career, and has partially used the concept to inform his work in co-authoring new diagnostic category of “Religious or Spiritual Problem” included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) 4 and DSM-5.

Lukoff suggests that although the term spiritual emergency, which is well-known in transpersonal psychology, is not used or necessarily accepted in mainstream circles, spiritual and religious issues are now becoming understood through different terminology.

“I think Stan and Christina nailed the concept, but as soon as you use the term ‘emergency’ in the healthcare field, it implies the worst case scenario in which a person might need hospitalization,” Lukoff tells Psychedelics Today. “The more neutral term ‘problem’ is now used within psychiatry as a result of the DSM category that I helped author, and the term ‘struggle’ is now used within psychology.”

Further, Lukoff emphasizes that he has seen a major shift, even though it is still a minority, in psychology and psychiatry programs on the coverage of religion and spirituality. “I know that the transpersonal world doesn’t always pick up on this, but there is a real renaissance within the healthcare field in which more attention is being heeded to religious and spiritual strengths as well as problems and struggles,” he says.

“There are definitely times when spiritual issues can become crises or conflicts, however, it is also true that for the majority of people their religion and their spirituality are sources of strength, more often associated with positive coping,” shares Lukoff.

In his early 20s, Lukoff experienced his own LSD-induced spiritual crisis in which he believed that he was a reincarnation of Buddha and Jesus, manifested in his present form to unite the peoples of the world. In part, Lukoff attributes his career trajectory as a clinical psychologist and professor of psychology to the psychosis-like transformational crisis he experienced early on.

Reflecting on his own psychedelic-induced spiritual crisis, Lukoff offers the view that careful preparation goes a long way in being able to mitigate the potential negative effects of psychedelics. Even so, it is important not to trivialize or reduce psychedelic-induced spiritual crises to conjectures about “bad trips.” Spiritual crises need not merely be the product of challenging psychedelic experiences as they can be similarly triggered by potent positive experiences.

Spiritual Crisis and The Future of Psychedelic Healing

Psychedelic healing is not linear. It is not as simple as popping a pill and being miraculously cured. Rather, it is a messy process which sometimes involves psychospiritual distress that is integral to the healing process. As medical and mainstream interest in psychedelic substances continues to expand, and more and more people have these kinds of experiences, it is imperative that psychedelic practitioners develop literacy around the concept of spiritual crisis, as well as develop frameworks to help individuals contextualize their challenging experiences.

With increased awareness and use of psychedelics, are practitioners ready to deal with some of the transpersonal experiences that clients will bring to them? Buller emphasizes the need for diverse and nuanced perspectives as we move forward into the psychedelic renaissance.

“While I appreciate the trauma focus and narrative in psychedelic research, I worry that we might end up reducing everything down to psychological terminology, discrediting a person’s experience,” he shares. “What happens when someone has an entity encounter in a psychedelic experience? Do we just reduce that experience down to a possible traumatic event in someone’s life or write it off as unreal because we have a mechanistic understanding of what that experience is?”

Moving towards the future, it is important to remain open-minded, and take holistic approaches that interweave multiple narrative frameworks, including that of transpersonal psychology, through which people can understand and make meaning of their experiences, including the potential for spiritual emergencies and their transformational—yet difficult—outcomes.

Dr. Devon Christie, MD, is a clinical instructor with the UBC Department of Medicine and has a focused practice in chronic pain. She is a Registered Counsellor emphasizing Relational Somatic Therapy for trauma, and a certified Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction teacher (UCSD) and Interpersonal Mindfulness teacher (UMass). She is trained to deliver both MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD (MAPS USA) and ketamine-assisted psychotherapy. She is passionate about educating future psychedelic therapists on trauma-informed, relational somatic skills and is co-founder of the Psychedelic Somatic Psychotherapy training program. She also teaches for the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS) Certificate Program in Psychedelic Therapy and Research, the Integrative Psychiatry Institute Certificate Program in Psychedelic Assisted Therapy, and the ONCA Foundation Psychedelic Therapy program. She is currently Principal Investigator and study therapist for a Canadian MAPS-sponsored open-label compassionate access study investigating MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD, co-investigator on a study investigating MDMA-assisted therapy for fibromyalgia, and is the Medical and Therapeutic Services Director with Numinus Wellness Inc.

Dr. Devon Christie, MD, is a clinical instructor with the UBC Department of Medicine and has a focused practice in chronic pain. She is a Registered Counsellor emphasizing Relational Somatic Therapy for trauma, and a certified Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction teacher (UCSD) and Interpersonal Mindfulness teacher (UMass). She is trained to deliver both MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD (MAPS USA) and ketamine-assisted psychotherapy. She is passionate about educating future psychedelic therapists on trauma-informed, relational somatic skills and is co-founder of the Psychedelic Somatic Psychotherapy training program. She also teaches for the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS) Certificate Program in Psychedelic Therapy and Research, the Integrative Psychiatry Institute Certificate Program in Psychedelic Assisted Therapy, and the ONCA Foundation Psychedelic Therapy program. She is currently Principal Investigator and study therapist for a Canadian MAPS-sponsored open-label compassionate access study investigating MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD, co-investigator on a study investigating MDMA-assisted therapy for fibromyalgia, and is the Medical and Therapeutic Services Director with Numinus Wellness Inc.

Robin Divine is a writer, psychedelic advocate, and the creator of

Robin Divine is a writer, psychedelic advocate, and the creator of

Matt Ball is a mental health nurse practitioner, psychotherapist, and founder of the

Matt Ball is a mental health nurse practitioner, psychotherapist, and founder of the

Pierre Bouchard is a Licensed Professional Counselor with a private practice in Boulder and Denver, CO. He specializes in blending somatics, embodiment, attachment theory, and trauma therapy with ketamine-assisted psychotherapy. A graduate of Naropa University (in Contemplative Psychotherapy), he has trained in several somatic psychotherapy modalities, most recently the Hakomi Method under Melissa Grace, and currently, in Ido Portal’s movement system at Boulder Movement Collective. He has maintained a meditation practice for 19 years, is working on opening a ketamine clinic, and in his spare time, works as a vinyl DJ.

Pierre Bouchard is a Licensed Professional Counselor with a private practice in Boulder and Denver, CO. He specializes in blending somatics, embodiment, attachment theory, and trauma therapy with ketamine-assisted psychotherapy. A graduate of Naropa University (in Contemplative Psychotherapy), he has trained in several somatic psychotherapy modalities, most recently the Hakomi Method under Melissa Grace, and currently, in Ido Portal’s movement system at Boulder Movement Collective. He has maintained a meditation practice for 19 years, is working on opening a ketamine clinic, and in his spare time, works as a vinyl DJ.

About Tim Cools

About Tim Cools

About Richie Ogulnick

About Richie Ogulnick

About Kile Ortigo

About Kile Ortigo

About Dena Justice

About Dena Justice

About the Entheo Society of Washington

About the Entheo Society of Washington

About JR Rahn

About JR Rahn

About Dr. Anne Wagner

About Dr. Anne Wagner

About VeronikaGold, LMFT

About VeronikaGold, LMFT About Dr. Harvey Schwartz

About Dr. Harvey Schwartz