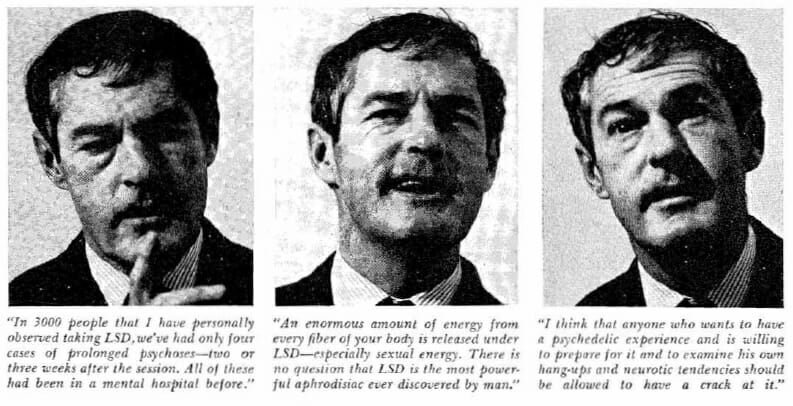

Joe Moore and Anne Philippi (New Health Club) are hosts of the PS25 Morning Show! This one features Dee Dee Goldpaugh, LCSW and Tommaso Barba, PhDC!

We talk about all things Sex and Psychedelics!

Joe Moore and Anne Philippi (New Health Club) are hosts of the PS25 Morning Show! This one features Dee Dee Goldpaugh, LCSW and Tommaso Barba, PhDC!

We talk about all things Sex and Psychedelics!

In this episode, Kyle interviews Tommy Aceto: former Navy Seal and trauma medic, and now, ambassador for the Veteran Mental Health Leadership Coalition and advisor at Beond Ibogaine.

He talks about how much the psychedelic space focuses on healing and mental health, but doesn’t talk enough about the overall wellness that can come from a consistent practice: that the more you become aware of your body, emotions, and breath, the more robust your neural pathways will become – and that you can actually change your neurochemistry and build a more energetically powerful system. With these pathways being opened, fewer psychedelic experiences are necessary, and with practice, these mind states can be achieved simply through meditation or breathwork. The idea of surrender and entering a state of receivership is scary, but he believes the most important skill to begin that transformation is to learn how to truly let go.

He also talks about:

and more!

Happy New Year from all of us at Psychedelics Today. Let’s hope for big psychedelic wins in 2025!

Ky.gov: Kentucky Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission

Veteran Mental Health Leadership Coalition

Filtermag.org: Kentucky Shelves Plan to Use Opioid Settlement Cash for Ibogaine Pilot

Nbcnews.com: One doctor vs. the DEA: Inside the battle to study marijuana in America

Peter Hendricks Ph.D. – Is Psilocybin Helpful For People Who Abuse Cocaine?

PT377 – Integrative Medicine: Health, Wellness, and Psychedelics, featuring: Andrew Weil, M.D.

Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art, by James Nestor

Psychedelic Education Center: End of Year sale

*Amazon links are affiliate links, meaning that Psychedelics Today will receive a percentage of the sale

In this episode, Joe interviews Melanie Curtis: world record professional skydiver, keynote speaker, coach, co-host of the Trust the Journey podcast, and author of How to Fly: Life Lessons From a Professional Skydiver.

Curtis shares her journey from taking her first transformative leap out of an airplane to becoming a leader in skydiving, public speaking, and now, the integration of psychedelics into personal growth. She discusses the parallels between skydiving and working with psychedelics – most notably in the idea of leaping into the unknown, trusting the universe, and in the potential that can be unlocked after you’ve come back down to earth. While relatively new to the psychedelic space, she stresses the importance of sharing your story and opening up dialogues, no matter how small you think your voice may be.

She talks about:

and more!

PT339 – Kim Dudine – Cannabis: The Gateway Drug to Unity Consciousness

The Hero’s Journey: Finding Your Story in Psychedelic Healing, featuring: Mareesa Stertz

Trust the Journey podcast: #127: Walking Each Other Home – Andy Lewis

How Boards Work: And How They Can Work Better in a Chaotic World, by Dambisa Moyo

How To Fly: Life Lessons from a Professional Skydiver, by Melanie Curtis

*Amazon links are affiliate links, meaning that Psychedelics Today will receive a percentage of the sale

In this episode, Joe interviews Paul Grof: research psychiatrist, clinician, author, brother of Stanislav, professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, and director of the Ottawa Mood Disorders Center.

He talks about his extensive career in psychiatry, and how trying to understand the cause of mood disorders led him to focusing on the very nature of consciousness. He believes that consciousness is a collaborative creation between the brain, body, and external fields, and that the key to connecting with the mechanistic side of academia is through talking about the unexplainable – near death experiences, pre-cognition, remote viewing – and of course, them having positive non-ordinary experiences through psychedelics or other means. He talks about how much we’re connected, how much our bodies remember, and how much society could change for the better if enough people experience the transpersonal.

He also discusses:

and more!

Sciencealert.com: Eerie Personality Changes Sometimes Happen After Organ Transplants

The Holographic Universe: The Revolutionary Theory of Reality, by Michael Talbot

Zimbardo.com: Life and Legacy of Psychologist Karl Lashley

Nasa.gov: What Is the Spooky Science of Quantum Entanglement?

Thelaszloinstitute.com: The Akashic Field with Ervin Laszlo – Higher Self Expo

*Amazon links are affiliate links, meaning that Psychedelics Today will receive a percentage of the sale

New ways of looking at non-ordinary experiences and integration are always being conceived. What is the 3-axis framework?

In this episode, Kyle interviews Pierre Bouchard, LPC, LM: therapist, minister, and former professional vinyl DJ specializing in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy and ministry.

Bouchard introduces his 3-axis framework for psychedelic integration, which looks at the personal, the transpersonal, and, with time, seeing how the lessons learned from non-ordinary experiences and personal work are expressing to the world: How can we use what we’ve learned to show up better? How can we use our gifts to be of service to others? What is stopping us? He also talks about the importance of building a foundation for holding the experience of a psychedelic journey – that you have to first build an ego to later dissolve it – but recognizes the tricky balance of not strengthening an ego so much that it gets in the way.

He discusses:

and more!

PT248 – Pierre Bouchard – Somatic Therapy, Trauma, and the Nervous System

Exploring Somatic Practices and Psychedelics, featuring: Pierre Bouchard, LPC & Kara Tremain, ACC

Deep-psychology.com: Ken Wilber Fundamentals: The Four Quadrants For Newbies

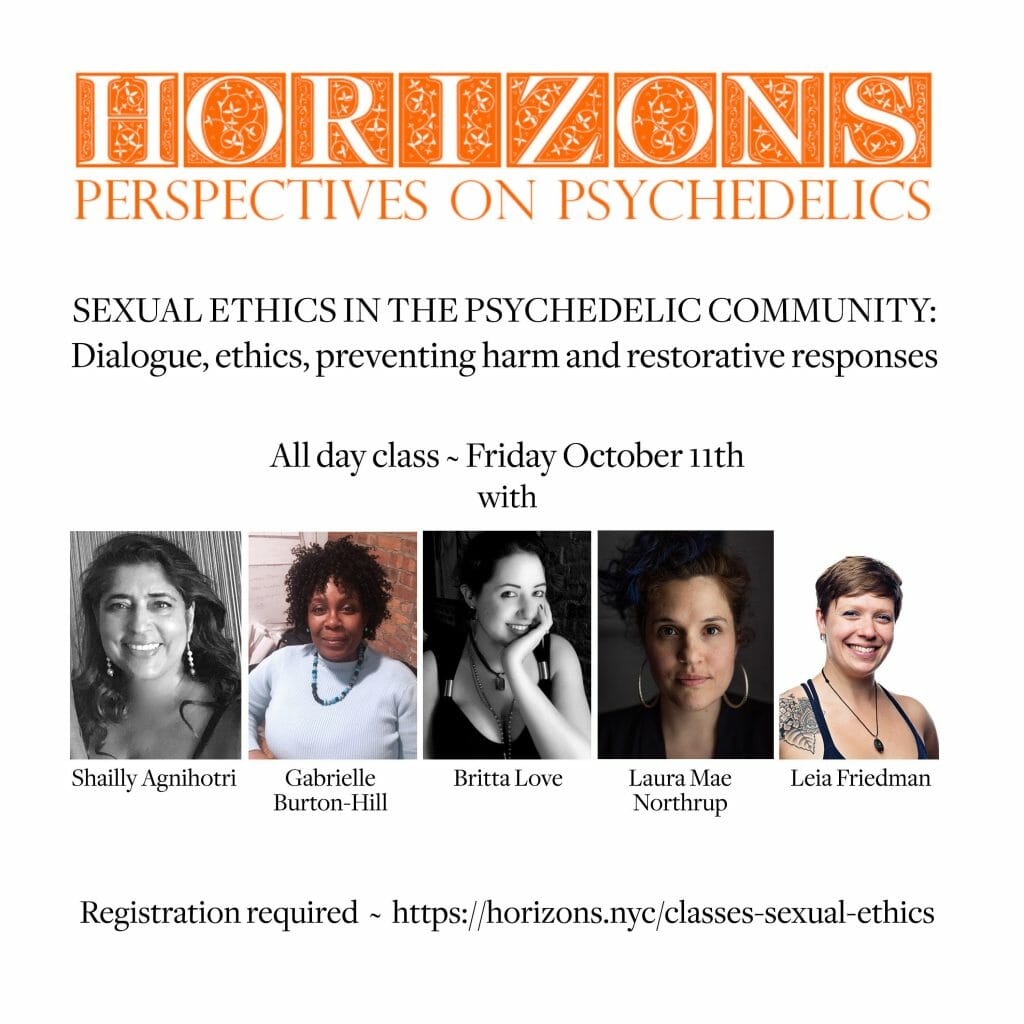

Can erotic energy be as transformative as a psychedelic experience?

In this episode, Joe interviews Bria Tavakoli, LPCC, MA, MS: a therapist specializing in relational and sex therapy, with a focus on helping clients integrate psychedelic experiences.

She shares her personal journey with psychedelics and how they unlocked deep trauma, allowing her to develop a level of comfort with intimacy, love, and her sexuality. She talks about the parallels between psychedelic journeys and sexual experiences, and how both can be gateways to unexplored parts of ourselves, as well as catalysts for healing and transformation. She discusses society’s cultural shame surrounding our sexuality, why we need to view sexuality from a wellness-based model, and how psychedelics can help couples grow together, and at times, really challenge their relational structures. When asked how to combine sex and psychedelics, she answers, “very carefully.”

She also discusses:

and more!

Embodywithbria.net: Share your story

YouTube: PT Live: Joe Moore and Tommaso Barba Discuss Sex and Psychedelics

Nature.com: Psychedelics and sexual functioning: a mixed-methods study

Mating in Captivity: Unlocking Erotic Intelligence, by Esther Perel

Laura Northrup – Healing Sexual Trauma with Psychedelics and Entheogens

Integrativesextherapyinstitute.com

Polysecure: Attachment, Trauma and Consensual Nonmonogamy, by Jessica Fern

*Amazon links are affiliate links, meaning that Psychedelics Today will receive a percentage of the sale

While the science of psychedelics is regularly discussed, the intersection of philosophy and psychedelics isn’t as much. Can an understanding of metaphysics bring more meaning to non-ordinary states?

In this episode, Joe interviews Dr. Peter Sjöstedt-Hughes: philosopher, lecturer at the University of Exeter, co-director of the Breaking Convention conference, and author who most recently co-edited Philosophy and Psychedelics: Frameworks for Exceptional Experience.

He discusses how the work of William James and an early psilocybin experience led him to an interest in philosophy and psychedelics, and he dives deep into several philosophical concepts: panpsychism, pantheism, ethical pluralism, teleology, process theology, Whitehead’s fallacy of misplaced concreteness, and more. He believes that science has lost touch with metaphysics – the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality – and that studying metaphysics will lead to more beneficial experiences with the non-ordinary: If you can understand and frame the experience, you’ll have a much better chance of being able to integrate its lessons.

He discusses:

and more!

Sjöstedt-Hughes is the co-lead on Exeter’s 12-month postgraduate certificate course, “Psychedelics: Mind, Medicine, and Culture,” and is finalizing his next book, a manual on psychedelics and metaphysics.

PGCert Psychedelics: Mind, Medicine, and Culture (Online)

Shroom: A Cultural History of the Magic Mushroom, by Andy Letcher

YouTube: Consciousness and psychedelics | Peter Sjostedt-H | TEDxTruro

The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature, by William James

Stanford.edu: Russellian Monism

Journalpsyche.org: Panexperientialism, Cognition, and the Nature of Experience

Neo-Nihilism: The Philosophy of Power, by Peter Sjöstedt-H

Comicbooknews.co.uk: Warren Ellis ushers Karnak into the Marvel Universe

The Center for Process Studies

Frontiersin.org: On the need for metaphysics in psychedelic therapy and research

The Holographic Universe: The Revolutionary Theory of Reality, by Michael Talbot

LSD Psychotherapy: The Healing Potential of Psychedelic Medicine, by Stanislav Grof, M.D.

*Amazon links are affiliate links, meaning that Psychedelics Today will receive a percentage of the sale

Psychedelic shadow work is central to the transformative potential of entheogens, helping us confront and integrate hidden parts of our psyche.

Psychedelic experiences, in and of themselves, do not create lasting change by chance or passively – they require active participation. Entheogens can open the doors to the unconscious and invite us to make meaning from its contents. Shadow work supports this soul-manifesting process by helping us embrace our hidden parts so that we may become fully actualized.

Psychotherapist Carl G. Jung coined the term “shadow” to describe the instincts, drives, and emotions we consciously and unknowingly repress but whose malignant impacts we feel.

The shadow contains our darkest secrets, covert desires, and obscured emotions. It holds our greatest fears and our fullest potential; it is the source of intuition, wisdom, and individuation. And yet, most of us reject it because we fear the truth – that we are both good and evil, loving and hateful, angry and calm, devastated and joyful, masculine and feminine.

“The shadow is a living part of the personality and therefore, wants to live with it in some form. It cannot be argued out of existence or rationalized into harmlessness,” said Jung in Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious.

Yet we disguise our undesirable traits, in part, to get along in polite society.

This process is necessary, according to the late psychedelic-assisted therapy pioneer Ann Shulgin. After all, we can’t enact our darkest fantasies of rear-ending every insufferable driver who cuts us off. We need executive control via the ego to quell such drives.

However, the issue arises when we overcorrect and deny our shadow’s existence.

When we hide from unflattering elements of ourselves, like aggression, guilt, power-hunger, and greed, we paradoxically give these traits more control over our lives. Unseen shadows show up unexpectedly, like when we lash out over minor frustrations, sabotage our career because of unacknowledged fears of success, or spout passive-aggressive remarks instead of confronting conflict directly. Unprocessed shame or guilt can manifest as perfectionism, and buried feelings of inadequacy may elicit a compulsive need to control.

“A man who is possessed by his shadow is always standing in his own light and falling into his own traps,” wrote Jung.

But just as we suppress unfavorable qualities, we also bury our brightest traits.

The “golden shadow” refers to these constructive qualities, such as confidence, creativity, compassion, leadership, and joy. We see these characteristics in others but sometimes fail to recognize them within ourselves because we feel unworthy, afraid of failure, or unfamiliar with how to embody them.

Kyle Buller, M.S., Psychedelics Today co-founder and psychedelic integration therapist, notes that many of us come from environments where positivity is unwelcomed.

“People may find it hard to experience joy because they associate it with guilt or shame, or they might feel that the therapeutic focus should be about the ‘darker emotions’ when it comes to shadow work. They may want to shut the good feelings down. This can be a great opportunity to work with the golden shadow,” said Buller.

Whether golden or dark, the shadow must emerge from hiding so we can reclaim our autonomy. But we must do the work to coax it out.

Ido Cohen, Psy.D. and lead instructor of the course, Navigating the Jungian Shadow with Psychedelics, defines shadow work as the practice of becoming conscious.

“We develop our ability to be aware and embody what we are conscious of,” Cohen told Psychedelics Today.

Psychedelics are one of the best ways to do this work because they “activate and amplify the psyche and our emotional, somatic and spiritual dimensions.” Dreams, hypnosis, and life transitions are also excellent catalysts.

Dreams

Jung believed dreams offer a direct path to the unconscious through their symbols. He suggested that themes like falling could represent a fear of failure, being chased might signify an unresolved conflict, and dark figures could convey unaddressed desires. He advocated that processing and analyzing such symbols illuminates the shadow.

Hypnosis

According to Ann Shulgin, Ericksonian hypnosis is another powerful shadow work method. This approach leads patients into a trance, where they descend a stairway deep into their inner world. When they reach the basement, they confront the shadow, which they see as a fierce animal. The hypnotist instructs them not to fear the beast but to enter its form and experience the world through its eyes. This merging allows them to harness the shadow as an ally rather than an enemy.

Transitions

Major life transitions, such as losing a loved one or experiencing a midlife crisis, can also ignite shadow work, whether we choose it or not. Such events break down our defenses and ego structures, leaving us vulnerable to repressed emotions, drives, and conflicts that demand our attention in order to grow.

Psychedelics

Psychedelic experiences are perhaps the most reliable path into the depths of our souls because they fundamentally change the way we think, feel, see, and perceive our inner and outer worlds. Entheogens teleport us directly beyond the ego’s veil into the unknown

“Psychedelics offer a unique opportunity to face our repressed parts head-on. They allow access in ways that regular psychotherapy may not,” said Buller.

Psychedelics help us access the shadow by disrupting the way our neural networks communicate and perceive stimuli. This process reduces activity in the brain’s default mode network (DMN), which governs our sense of self and ego.

When the DMN quiets, boundaries between consciousness and unconsciousness blur. The resulting experience excavates stifled thoughts, memories, emotions, and visions while allowing us to interact with them from an open and receptive state.

Shadow work can happen naturally during these journeys. We might even transcend the unconscious labels of “good” vs. ” bad” while stepping outside our sticky parts to merge with something greater than ourselves. Such interconnected insights are transformative, but they are not necessarily the norm.

Psychedelics often reveal harrowing traumas and wounded parts that we may be unskilled to face. This confrontation can spark intense anger, grief, or shame. Our ego will resist the discomfort to protect us, but its efforts will paradoxically exacerbate it. We may become overwhelmed, overly identified with the pain, or completely detached from reality.

These very real risks are a crucial reason navigating the shadow with psychedelics often requires support, especially when we’re inexperienced with these substances.

Psychedelic-assisted therapy, preparation and integration coaching, and group processing provide critical foundations to face and embrace unconscious aspects of the self.

Skilled practitioners know how to hold space for every part of us to emerge. If we’re experiencing unresolved rage, therapists or facilitators can help us feel and release it.

“Anger is a major emotion that people often struggle to express. We [as practitioners] might ask, ‘What would it look like to express this anger?’ It could mean yelling, shaking, or verbalizing. Clients may even direct anger toward the therapist in place of the person they’re really angry at,” said Buller, who added that projections are O.K. within the confines of the practitioner’s comfort and safety boundaries.

Psychedelic facilitators also invite us to stick with the feelings we may want to oppose.

“When clients experience discomfort, we might ask, ‘Can you find pleasure in this sensation?’ Sometimes, the edge of discomfort is where the real work begins,” said Buller.

Buller explains that from a holotropic breathwork perspective, amplifying emotional expression is the key to expunging it from our system.

However, the edge is sometimes too dangerous to approach, and effective practitioners know when to pull back the reins.

“We don’t push shadow work agendas on clients. If you go too quickly, the parts might rebel. Instead, we take a slow approach and partner with the client so they can eventually go deeper,” said Buller.

This alliance allows practitioners to determine when digging into the shadow’s contents is appropriate and when it could inflict harm.

After confronting the shadow, we must begin the process of integration, where we interpret and act on our findings. Some of the most effective integration methods involve working with a therapist, coach, or support group.

“Ideally, we want to start with a safe process of slowly digesting our psychedelic insights. We can then form a relationship of curiosity, inquiry, and then change,” said Cohen.

The change piece can be the most challenging because it mandates that we rewire our lives to match the authentic selves we’ve been hiding for so long. We may need to quit a job, end a marriage, or restructure relationships with friends, family, and substances. Such radical shifts often require reliable help and compassionate accountability.

Therapists trained in psychedelic integration, especially those using frameworks like Jungian analysis or Internal Family Systems (IFS), are well-suited for effective shadow work because they provide a structured approach to processing unconscious material.

Jungian therapists can help interpret the symbolic messages of psychedelic visions, such as the tiger, whose archetype might signify repressed feminine essence, aggression, or independent spirit.

Analysts can also help us make sense of bodily sensations, postures, memories, and emotions.

“We then want to understand the shadow material within the larger context. How was it formed, what’s its use, and more. This will allow us to start weaving together a narrative, opening us to intergenerational and environmental influences and having more compassion with ourselves,” said Cohen.

In the context of IFS, therapists can help us integrate the shadow using parts language. They may guide us in understanding that the tiger is a protector part, fiercely defending our vulnerable exiled parts, such as our traumatized inner child from suffering. Such terminology prevents us from overidentifying with the stifled rage and allows for a more harmonious and balanced sense of self.

Psychedelic shadow work is transformative, especially in the context of powerful journeys and integration. It provides a framework for understanding the visions, sensations, and thoughts that arise during altered states of consciousness and invites us to engage further. In turn, psychedelics calm our ego and amplify our psyche so we may embrace our inner outcasts as missing puzzle pieces to the fullest expression of our humanity.

Telling our stories of psychedelic healing is more important than ever, but sometimes, those stories aren’t so clear cut. Can applying the classic archetype of the Hero’s Journey to your narrative help you find your story?

In this episode, Joe interviews Mareesa Stertz: lead of strategy/communications at the Global Psychedelic Society, co-founder of Lucid News, and filmmaker, currently finalizing her second feature film, “Confessions of a Psychonaut.”

She discusses her path to wanting to create the film: how she always felt like something was wrong with her but didn’t know exactly how to start her healing path, how seven ayahuasca trips didn’t give her the breakthrough experience she wanted, and how she realized over time that she didn’t have a hidden moment of trauma to overcome, but rather, lots of “little t” trauma – something that a lot of us have, without necessarily knowing it. She saw the true power of people sharing their stories of becoming healthier, and has found that aligning our stories to the classic framework of the Hero’s Journey and Carl Jung’s concept of individuation is the perfect formula for self-awareness, growth, and finding more meaning in life.

She talks about:

and more!

Stertz is passionate about creating a culture that celebrates healing, and believes the biggest thing we can all do is to share our stories. She’s offering a course on finding where the Hero’s Journey is in each of our lives: “Emerge: A Journey of Self-Authorship” begins on October 29. Click here for more info.

Upcoming storytelling course: Emerge: A Journey of Self-Authorship

”Confessions of a Psychonaut” trailer

Indiegogo.com: Help bring “Confessions of a Psychonaut” to the big screen

Lucid.news: Adventures of the Psyche

Azquotes.com: Albert Camus’ suicide quote

Socratic-method.com: Pliny the Elder’s “depth of darkness” quote

Templarhistory.com: Eliphas Levi: The Man Behind Baphomet

This online hybrid live course delves into the profound realms of the human psyche, drawing upon the pioneering work of Carl Jung, the transformative potential of psychedelics, and the intersection of the two worlds. Participants will embark on a journey to understand the concept of the “Shadow” – the hidden, unconscious aspects of the personal psyche and the collective – and explore how psychedelics can serve as tools to illuminate and integrate these often-neglected facets of our being.

Class meets on Wednesdays, for 8 weeks, from 9:00 – 11:00 a.m. PST / Noon -2:00 p.m. EST, beginning on Oct. 30, and continuing until Dec. 18.

By taking this course, you will learn:

Taught by Dr. Ido Cohen, Kyle Buller, M.S., Johanna Hilla-Maria Sopanen, and Marc Aixalá. Head to the course page in the Psychedelic Education Center for more info.

While the concept is often unfairly reduced to replacing one drug with another, many people struggling with addictions are proving that there’s a positive link between the use of psychedelics and addiction recovery. Can microdosing be a factor?

In this episode, Joe interviews Danielle Nova: founder of Psychedelic Recovery, founding team member of Decriminalize Nature Oakland, and Executive Director of the San Francisco Psychedelic Society.

As a recovering addict, Nova discusses how working with psychedelics helped her find her way to recovery, and how she’s spreading that knowledge to others through her Psychedelic Recovery program, which focuses more on ‘targeted abstinence,’ instead of the total abstinence model of Psychedelics In Recovery (which works alongside AA’s 12-step program). She believes that it’s extremely important to reframe addiction as a life process or temporary state of consciousness (rather than a life sentence you can’t escape), and that beating addiction is not about constantly being afraid of a relapse, but about evolving to a state of empowerment: that you can overcome it, and that actually, a horrific addiction may have saved you and brought you to where you’re supposed to be.

She discusses:

and more!

She has co-created Microdosing Facilitator Training with Adam Bramlage of Flow State Micro: a first-of-its-kind 4-month program teaching clinicians, facilitators, and coaches about microdosing and how to safely guide others through the practice. The next cohort launches in January 2025.

Microdosingfacilitatortraining.com

Nature.com: Low doses of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) increase reward-related brain activity

PT303 – Adam Bramlage – Cannabis, Microdosing, and Our Evolutionary Connection to Psychedelics

How Long Does A Microdose Last? by Elena Schmidt

Nih.gov: Valvular Heart Disease with the Use of Fenfluramine-Phentermine

Modern Western culture has conditioned us to suppress our feelings and bury negativity, exacerbating any existing trauma and often creating more. With the rise in popularity of psychedelic-assisted therapy, just how important is it for practitioners to be trauma-informed?

In this episode of Vital Psychedelic Conversations, David interviews Deanna Rogers: Registered Clinical Counselor and Vital instructor.

She discusses how trauma grows in our bodies, and the importance of practitioners and facilitators becoming trauma-informed before working with clients. She stresses the need to create the right conditions for clients to be able to work with trauma – to bring compassion to the different parts of their self and build a relationship with the uncomfortable ones, to interrupt negative narratives, and to learn how to exist in a place where they can embrace their window of tolerance and explore discomfort in a safe way. What is the specific container and pace each client needs? How flexible is their nervous system to be able to work with these states? What can be done to bring out the empathetic witness in themselves? And most importantly, how can their sense of agency be improved so that they feel like they’re fully in control of how deep things go?

She discusses:

and more!

Rogers is one of our Vital instructors, featured in one of Vital 4’s new Specializations: Somatics & Trauma. This cohort begins on September 17, and the application deadline is next week, September 3, so apply today before it’s too late!

Somethinkofvalue.com: 70 Gabor Maté Quotes About Trauma, Healing, and More

Goodreads.com: Peter Levine quote

PT302 – Dr. Adele Lafrance – Vital Psychedelic Conversations

There are many different aspects to consider when integrating a psychedelic experience, and many tools to help, like engaging in shadow work, practicing meditation, and even applying teachings from Buddhist philosophy.

In this episode of Vital Psychedelic Conversations, Vital instructor, Diego Pinzon hosts his first podcast, interviewing Vital graduate and clinically-trained psychologist, “The Kinki Buddhist”: Kate Amy.

As Amy’s interest in psychedelics grew, she began to see a clear intersection between psychedelic states and the non-ordinary states she’d reached through years of meditation practice, as well as lessons from Buddhism that could help in better understanding psychedelic journeys. She talks about the importance of really understanding what it is one is seeking when looking to have a psychedelic experience, and the significance of integration – no matter how long it takes. While she has tips that have worked for clients, she feels that the psychedelic space has a long way to go in establishing best practices for the most effective integration.

She discusses:

and of course, her experience with Vital!

The deadline for submitting your application is next week, August 23, so make sure to get your application in today.

Mindworks.org: The 5 Precepts Of Buddhism And Why They Matter

Jungian psychology takes a fascinating look at the relationship between the conscious and unconscious parts of our minds. How is this framework brought more to the forefront through psychedelics and an understanding of our many parts?

In this episode of Vital Psychedelic Conversations, Johanna interviews Jung experts and Vital instructors: Maria Papaspyrou, psychotherapist and co-founder and director of the Institute of Psychedelic Therapy (IPT); and Dr. Ido Cohen, clinical psychologist and founder of The Integration Circle.

They talk about the experiences that helped them first understand the concept of multiple different parts making up their being, and dive into what it is about psychedelics that allows us to discover and work with these different parts: how the protector parts of our psyche work overtime to keep parts away from us, and how psychedelics can dissolve them, leading to a better understanding of ourselves. How much of our persona is based on who we feel we’re supposed to be? What shadow parts are stopping us from being our true selves? And what amazing parts of ourselves have yet to be discovered?

They discuss:

and more!

If you really want to dig into Jungian ideas, Jungian psychology is one of the new specialization tracks featured in the next cohort of Vital, beginning September 16. If you want to know more, send us an email or attend one of the next Vital Q+As.

Instituteofpsychedelictherapy.org

PT390 – Vital Psychedelic Conversations, featuring: Mackenzie Amara & Dr. Ido Cohen

PT450 – Dreams, Psychedelics, Symbolism, and Cockroaches, featuring: Mackenzie Amara & Dr. Ido Cohen

Lithub.com: The Heteronymous Identities of Fernando Pessoa

My Self, My Many Selves, by J.W.T. Redfearn

*Amazon links are affiliate links, meaning that Psychedelics Today will receive a percentage of the sale

What are bad trips, or adverse, negative, or challenging experiences? Can a definition truly define the power they have to create intense distress and sometimes life-defining moments? Why do they happen, and how do you deal with them?

In this episode, Joe interviews Erica Rex, MA: award-winning journalist, past guest, thought leader on psychedelic medicine, and participant in one of the first clinical trials using psilocybin to treat cancer-related depression.

She tells the story of her recent harrowing experience, brought on by 6 times the amount of Syrian rue that was recommended: from entities threatening her, to a sense of terror she was going to die, to finding her way out of it with time, and most importantly, context to process and a strong support system. She and Joe emphasize the reality that bad trips can happen at any time, with any dose, for any reason, and that – if you can make your way through the experience without being traumatized – you can learn a lot about yourself during those states.

Her book, “The Heroine’s Journey: a woman’s quest for sanity in the psychedelic age” will be published by She Writes Press in the spring of 2026.

She discusses:

and more!

Psychedelicrenaissance.substack.com

National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute: A Breast Cancer Patient’s Perspectives on the Uses of Psychedelics in Medicine (Erica’s talk starts at 1:04:41 and lasts about 44 minutes)

PT273 – Erica Rex – Clinical Trials and Spontaneous Mystical Experiences

Could the Sonoran Desert Toad Cure Narcissism? by Erica Rex

Chacruna.net: DEA Denies Soul Quest’s Religious Exemption: Impacts on the Ayahuasca Community

An Inside Look at the FDA and Early Drug Development, featuring: Dr. Amanda Holley

Lykospbc.com: Lykos Therapeutics Statement on FDA Advisory Committee Meeting

Nih.gov: Persistent Psychosis After a Single Ingestion of “Ecstasy” (MDMA)

Goodreads.com: Albert Camus’ quote about suicide

Although the late psychologist and mystic Carl Jung died in the 1960s, his ‘inner self’ legacy is enjoying an organic revival, synchronizing with the resurgence of psychedelics.

Jung’s work provides a reliable road map for a psychedelic trip through the unconscious, and contemporary psychedelic explorers are hungry to learn more about his profound teachings.

Jung’s enduring transpersonal principles can help us interpret and understand complex non-ordinary experiences, whether they’re brought on by psychedelic compounds or other endogenous methods.

Thus, his insights resonate with a broad audience: licensed therapists, reiki practitioners, guides, yogis, integration coaches, breath workers, and others.

“We’re in need of tools that help us to articulate what’s going on at that level of depth,” says Jungian analyst-in-training and clinical psychology doctoral student MacKenzie Amara. “…we don’t have [many tools] to articulate what’s happening when we get into the messy place of extreme emotional catharsis and symbolic representation through the form of visions and communication with ancestors who have been long dead.”

In order to comprehend Jung’s psychospiritual philosophies, it’s crucial to first understand some basic Jungian concepts and terms. Jung believed that the psyche (mind, body, soul) is composed of three parts: the ego (or personal conscious), the personal unconscious (unique, containing suppressed memories), and the collective unconscious.

The collective unconscious is a domain of primordial images and symbols that evoke meaning and connection across races, cultures, and nationalities. According to Jung, these symbols contain ‘ancestral memory’, which is inherited. Our ancestral roots and dreams provide insights into the collective unconscious, which shapes our perceptions, knowledge, and experiences.

Within this realm, four main archetypes reflect our beliefs, values, motivations, and morals. The four main Jungian archetypes are:

Due to intense engagement with archetypes during psychedelic experiences, individuals risk having their personal worldviews disassembled in the process.

“Jungian theory lends itself to people that have had spiritual, transgressive, or transpersonal experiences more than those that are kind of stuck in a rational materialistic worldview,” Amara explains.

These transpersonal experiences make the Self the focal point of the journey of individuation.

The Self is central to Jung’s worldview, merging consciousness and unconsciousness to represent the whole psyche. We are born with a sense of unity, but as we grow and focus on the outer world—school, work, relationships—we form an ego and lose this unity, neglecting our inner world.

Jung identified two life stages: the outer world and the inner world. As adults, we often experience tension between our conscious and unconscious minds, leading to a midlife crisis. This signals the need to nurture our inner life.

Life’s challenges can bring a “dark night of the soul,” where societal values fail us. This prompts a quest to reconnect with our soul, though many avoid this confrontation. Embracing our suffering can lead to psychic growth, uniting our conscious and unconscious realms.

Through this process, known as individuation, we integrate the ignored parts of our unconscious, regaining wholeness and inner harmony.

As we turn inward, we encounter individuation, a central theme in Jung’s work. Individuation integrates our unconscious with the conscious, restoring the wholeness of the Self. This process, akin to self-actualization, involves breaking free from societal and cultural norms to become a unique individual. Successful individuation provides deep-rooted stability, like an ancient oak tree, supporting us through life’s storms.

Individuation heals the split between the conscious and unconscious, allowing our true Self to emerge. This journey creates turbulence as we realize our conventional world and unconscious world often conflict. The conventional world shapes our beliefs and behaviors, creating a structured reality. In contrast, the unconscious is chaotic and tumultuous, divided into the personal and collective unconscious. The personal unconscious contains everything outside our conscious awareness.

From birth, we operate largely on autopilot, influenced by external conditioning. This conditioning shapes our ego and self-perception, leading to a split and psychic imbalance. Psychedelics can help repair this split, aligning our conscious and unconscious minds.

Carl Jung coined an often used term in psychedelic vernacular: ego death. Ego death refers to a compromised sense of self, and it’s a state that’s coveted by many psychonauts. While some consider it an end goal of psychedelic work, it’s really the first step towards a return to wholeness. So, why is this idea prevalent in the psychedelic community?

“Psychedelics are what we call psycho-pumps for individuation. Meaning psychedelics are connectors to personal and collective unconscious; what gives you more of the unconscious material to then work with,” Dr. Ido Cohen explains.

This idea results in the common sentiment that psychedelics are “ten years of therapy in one day.”

While Cohen doesn’t think it’s necessarily accurate, he believes people are trying to say, “Wow, psychedelics can really open up the barrier to the personal and collective unconscious which then a flood of information comes in.”

This shedding of a one-sided self-identity holds true in above ground and underground psychedelic settings, as people jump-start their individuation. Insights can follow that may lead a person to explore what has been relegated to the basement of their psyche, or the “shadow.” When we learn to dance with the shadow, we empathize and relate with all of mankind on a profound level, Cohen says.

As a midlife crisis arises, or we enter a dark night of the soul, and the process of individuation begins and we come face to face with our shadow. This daunting task is referred to as doing “shadow work,” (another Jungian term gaining popularity in licensed and underground settings alike).

At first glance, we may see our shadow and assume it is evil or an enemy. But our shadow is part of us, and can’t be abandoned or avoided. As we familiarize ourselves with the shadow, we learn that it is not to be feared, as it is only dark or hostile when it is ignored or misunderstood. Thus, it’s critical to understand what the shadow really is.

The shadow encompasses all the psychic elements we reject and hope to discard by casting them into the depths. It includes the traits we’ve ignored, disowned, or removed from ourselves, forming our personality in the process. The shadow is the unknown dark side of our personality, representing everything we desire not to be.

The shadow includes negative and primitive human emotions and impulses: selfishness, rage, greed, pride, and lust. Anything we reject in ourselves as evil, intolerable, or less than ideal forms the shadow. It’s a repository of both negative and positive qualities we no longer claim. Within this mix, we find the shadow’s hidden treasures.

Cohen notes, “There is also the golden shadow, which includes beautiful aspects we repressed due to our upbringing or environment.”

This could mean rediscovering playfulness or sexuality. Or it could reveal latent talents, like a lawyer discovering a talent for writing or an athlete becoming a chef. It often emerges in psychedelic settings, inspiring life changes like new careers, divorces, or relocations. However, it’s crucial to provide quality integration and a solid container to help individuals make sound decisions and avoid regret.

The shadow compensates for what we lack. For instance, if a person is aggressive, the shadow reflects empathy and tenderness. If they’re shy, it reflects confidence and assertiveness. Honoring and accepting the shadow is an intense spiritual exercise, revealing our potential and the ideal self we strive to become.

For the Western mind, unaccustomed to Indigenous worldviews that embrace plant spirits and entities, Jung’s concept of the inner self offers all psychedelic practitioners an invaluable tool to navigate the mind-manifesting unknown. Think of Carl Jung as a trustworthy psychic sherpa: he guides us through the peaks and valleys of the timeless and boundless realms of human consciousness (and unconsciousness), helping us reconnect with our soul.

In this episode of Vital Psychedelic Conversations, David interviews Casey Paleos, MD: Vital instructor, researcher, psychiatrist with a private practice offering ketamine infusion therapy and KAP, and co-founder of Nautilus Sanctuary, a non-profit psychedelic research, education, and advocacy organization.

Paleos talks about how stress creates trauma, and how the symptoms Western medicine tries to silence are actually signals – a quality assurance mechanism sending an alert that something is wrong, and that when symptoms are labeled as ‘treatment-resistant,’ is it actually a case of one’s own inner healing intelligence outsmarting a medication to make sure that that message is delivered?

He discusses:

and more!

Verywellmind.com: What Is the Diathesis-Stress Model?

Lykospbc.com: Lykos Therapeutics Statement on FDA Advisory Committee Meeting

Nautilussanctuary.org: The Dana Paleos Fund

Mymodernmet.com: Kintsugi: The Centuries-Old Art of Repairing Broken Pottery with Gold

In this episode, Kyle interviews Peter A. Levine, Ph.D.: developer of Somatic Experiencing®, educator, and author of several best-selling books on trauma.

His most recent book, An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing Journey, is exactly that: a change from more scholarly writing into an extremely vulnerable telling of his early childhood trauma and how he has healed over the years. He talks about how his unconscious convinced him to write the book, how trauma can move into the body, and how he needed a student to identify how his trauma was affecting him. He believes that we all have wounding, but it’s how we carry these wounds and tell our truth that matters.

He discusses:

and more!

An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing Journey, by Peter A. Levine

Ted.com: How to live passionately—no matter your age

YouTube.com: The Moth Presents Andrew Solomon: Notes on an Exorcism

YouTube.com: Marvin Gaye – It Takes Two

Navigating Psychedelics: Australia – 9-Week Certificate Program in Psychedelic-Informed Practice

*Amazon links are affiliate links, meaning that Psychedelics Today will receive a percentage of the sale

In this episode, Kyle interviews Simon Yugler: psychedelic-assisted therapist, educator, and author of the book, Psychedelics & the Soul: A Mythic Guide to Psychedelic Healing, Depth Psychology, and Cultural Repair, which comes out this fall.

He digs into depth psychology and why it’s a beneficial framework for navigating non-ordinary experiences – a practice he believes will be the next focus in psychedelic education and understanding, alongside more analysis into the archetypes and myths that reside within (and all around) us. In an age of hyper-individualism and isolation, the stories and archetypal energies we share (which can be brought more to the forefront with psychedelics) can be incredibly healing and connecting.

He discusses:

and more!

What Is Depth Psychology and How Does It Relate to Psychedelics? by Simon Yugler

PT293 – Stanislav & Brigitte Grof – The Evolution of Breathwork and The Psychology of the Future

Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View, by Richard Tarnas

The Origins of Creativity, by Edward O. Wilson

*Amazon links are affiliate links, meaning that Psychedelics Today will receive a percentage of the sale

In this episode, David interviews Sami Awad: Palestinian peace and nonviolent activist and founder of Holy Land Trust in Bethlehem; and Leor Roseman, Ph.D.: Israeli neuroscientist, researcher, and senior lecturer at the University of Exeter.

They talk about Roseman’s 2021 paper, “Relational Processes in Ayahuasca Groups of Palestinians and Israelis,” which looked at what happened when people with fiercely different opinions moved beyond fear, anger, and othering, and sat together in a safe container and drank ayahuasca with the purpose of healing collective trauma. When the focus of the participants moved toward understanding each other, Roseman and Awad saw a unity that gave them a lot of hope, leading to the creation of their nonprofit, RIPPLES, which is focused on using psychedelics for peacebuilding – first in the Middle East, and hopefully soon, everywhere. As Awad says, “If it can happen here, it can happen almost anywhere.”

They discuss:

University of Exeter: Dr. Leor Roseman

Frontiersin.org: Relational Processes in Ayahuasca Groups of Palestinians and Israelis

In this episode, Joe and special guest, Court Wing, interview Tommy Aceto: former Navy Seal and trauma medic, NCAA athlete, Michigan State Champion Wrestler, and now, psychedelic advocate and ambassador for the Veteran Mental Health Leadership Coalition.

He discusses his journey from childhood to wanting to become a SEAL, and the toll that military life and its programming can take on a person: how a life built on high levels of endurance, deprivation, and constantly surviving in a fight-or-flight mindset often manifests in Operator Syndrome, chronic pain, depression, and addiction. Veterans are seeing the potential of psychedelics to rewire their brains and allow them to process pain differently, by allowing them to feel emotions they were trained to turn off: “You’ve got to feel to heal.”

Aceto discusses:

and more!

YouTube: Journey – Only the Young

The Breakthrough Therapies Act

Royalsreview.com: Remembering Mike Sweeney

Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs, by Johann Hari

Si.com: The Ugly End of an All-Pro Career, the Uglier Start of a Life After Football

The Rose Of Paracelsus: On Secrets & Sacraments, by William Leonard Pickard

Book links are affiliate links, meaning that Psychedelics Today will receive a percentage of the sale.

In this episode, Joe and Kyle interview Lenny Gibson, Ph.D.: philosopher, Grof-certified Holotropic Breathwork® facilitator, 20-year professor of transpersonal psychology at Burlington College, and the reason Joe and Kyle met many years ago.

He talks about his early LSD experiences and how his interest in the philosophy of Plato and Alfred North Whitehead provided a framework and language for understanding a new mystical world where time and space were abstractions. He believes that while culture sees the benefits of psychedelics in economic terms, the biggest takeaway from non-ordinary states is learning that value is the essence of everything. And as this is being released on Bicycle Day, he discusses Albert Hofmann’s discovery and whether or not it’s fair to say that Hofmann intentionally had the experience he did on that fateful day.

He also discusses:

and more!

PT316 – Lenny Gibson, Ph.D. – Vital Psychedelic Conversations

Science and the Modern World, by Alfred North Whitehead

LSD: My Problem Child – Reflections on Sacred Drugs, Mysticism and Science, by Albert Hofmann Ph.D.

The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell, by Aldous Huxley

Shadow Culture: Psychology and Spirituality in America, by Eugene Taylor

Book links are affiliate links, meaning that Psychedelics Today will receive a percentage of the sale.

In this episode, Joe interviews Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris: founder and head of the Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London, founding director of the Neuroscape Psychedelics Division at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and founder of the Carhart-Harris Lab.

A legendary researcher, he talks about his psychedelic origins: studying Freud, Jung, and eventually Stan Grof and depth psychology to try and better understand the unconscious. He discusses the growth of psychedelics and the cultural shifts he’s noticed (especially in the U.S.), as well as what he’s working on today: researching the influence of psychedelics on set and setting by studying experiences in both enriched and unenriched environments.

He also talks about:

and more!

UCSF is seeking survey volunteers, so if you’ve had more than three experiences with ketamine, MDMA, and psilocybin (must have experiences with all three) and want to contribute, do so here.

“In my school of thought, that’s not the problem, that’s the opportunity. When something makes sense but it’s abstract, I’m more led by the fact that it makes sense. The abstraction is an opportunity. It’s a richness, a fertility, and we can really dig into that.”

“You notice when people really put mindfulness to the aesthetic, and they lower the lights and with the music: it doesn’t take long and that much effort, really, before it starts to feel like really caring – like actively caring. And it is an intriguing thing to think that that’s absent in the default, you know? That’s a thing that a colleague said to me once; that she loved the fact that psychedelic therapy brought back care. As someone who went into the mental health care profession, she felt like she could care again, for the first time in a long time. And that was not just ok, that was really promoted and made easier in a sense by the paradigm.”

“There’s different hierarchical levels to these assumptions, but the assumptions are often the problem. They guide our experience of the world, but they can entrench us in certain ways, and that entrenchment can be really at the heart of a lot of psychopathology, a lot of mental illness.”

“I guess one thing I’ve discovered, which is fantastic, is just seeing how broad the community is here around psychedelics, and generationally as well. In London, it was really just a young generation, but here, it really transcends generations, and I really appreciate that. There’s something very normalized about psychedelics here that I started noticing very early on; that it was a topic of polite conversation. …That felt like a glimpse of how it will be, not just here, but elsewhere in the future.”

Fill out UCSF’s survey (must have 3+ experiences with ketamine, MDMA, and psilocybin)

PT245 – Robin Carhart-Harris – Psychedelics, Entropy, and Plasticity

The Dream Drugstore: Chemically Altered States of Consciousness, by J. Allan Hobson

Pnas.org: Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin

PT389 – The Art of Ecstasy: The 90’s British Club Scene and MDMA, featuring Rupert Alexander Scriven

In this episode, David interviews Saga Briggs: freelance journalist and author of How to Change Your Body: The Science of Interoception and Healing Through Connection to Yourself and Others.

A collection of interviews, peer-reviewed research, and personal story; the book dives deep into the mind-body connection, how to become more embodied, and our need for social connection – which factors into mental and physical health far more than most of us realize. The nod to Michael Pollan’s book is also a challenge: Have we been focusing too much on our minds and now it’s time to pay more attention to our bodies? How much of the benefit of psychedelic experiences is related to truly experiencing our bodies?

She discusses:

and more!

“I think people are familiar with the ways in which different compounds can influence the bodily self, so to speak. And it’s a really interesting idea that that, in and of itself (the modulation of your body or your experience of your body or how the body is represented by the brain): if that maps onto therapeutic outcomes, if that’s part of what’s so beneficial about these compounds – not just changing neural pathways in the brain, but actually giving you a different experience of yourself as an embodied organism in the world – I think this is a really interesting area to look into.”

“The minimal self is kind of just your basic feeling of being in a body, not necessarily tied to your identity. And the narrative self is like the story you tell yourself: who you are when you wake up in the morning, all of your memories, and kind of your life story. And it seems that there’s something going on with psychedelics where the minimal self: its influence sort of traverses over the narrative self, and we get an opportunity to be re-embodied in a way.”

“I don’t see a separation between a place of calmness within my body and the peace of the natural world. It’s the same quality to me. So if I’m standing, looking up at the stars at night in some beautiful remote place, that resonates inside me because it’s the same quality, if that makes sense. I feel it in my body so profoundly because it’s a reminder that my body is part of this greater profound stillness.”

Sagabriggs.journoportfolio.com

The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, by Bessel Van Der Kok, MD

Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA)

Biorxiv.orgThe entropic heart: Tracking the psychedelic state via heart rate dynamics

In this episode, Joe interviews Christine Calvert: Licensed Chemical Dependency Counselor and certified Holotropic Breathwork® facilitator.

She talks about how addiction led her to breathwork, how breathwork has helped her over the years, how breathwork can be a compliment to other self-work, and how becoming comfortable with breathwork first could be a very important stepping stone towards better understanding the psychedelic experience. She talks about how years of breathwork helped her navigate complicated states of consciousness, and the incredible benefit of learning to trust our body’s capacity to heal itself.

She discusses using bodywork in sessions and the importance of having the experiencer be the one who requests it; how much a facilitator’s past relationship with touch affects how they use touch; the risk in meditation vs. the safety of breathwork; the concept of learning self-awareness; how profound it is to be witnessed in breathwork’s dyad model; and why researching and creating guidelines for this kind of work seems impossible.

“One of the things I love so much about breathwork vs. psychedelics is that it is endogenous medicine; this is coming from within me. And as somebody who had experienced the world in [a way that] felt like I really was surrounded in a culture and a society that was incredibly disempowering – to have a model that turns you back inside yourself over and over again is a true gift and an act of radical self-empowerment.”

“Obviously in counseling we get witnessed, but there is something really profound about the witnessing in the dyad setup model of holotropic breathwork where [we’re] being witnessed by somebody, and their job is only to do that: to literally sit [and] accompany me as I go internal. And then there’s just an immense amount of support. So for these parts that really didn’t have support and are holding a lot of the trauma of omission (the things we needed that we didn’t get); it’s incredibly powerful and poignant to have this kind of relational field surrounding us through that while that material is moving through us.”

“I feel like if we could do a stepping stone program, breathwork would be the first one, because I think if we can’t access and understand what and who we are with our own endogenous medicine; as explorers and facilitators or practitioners, I think we’re missing something.”

The Thirst for Wholeness: Attachment, Addiction, and the Spiritual Path, by Christina Grof

In this episode, Kyle interviews John H. Buchanan, Ph.D.: certified Holotropic Breathwork practitioner; contributing co-editor for Rethinking Consciousness: Extraordinary Challenges for Contemporary Science; and author of the new book, Processing Reality: Finding Meaning in Death, Psychedelics, and Sobriety.

Recorded shortly after a week-long philosophy and breathwork conference which they both attended, they mostly dig into the challenging philosophical concepts of Alfred North Whitehead: how everything is made up of a feeling; how everything is relational and we all feel each other’s experiences; how Whitehead defined occasions and how moments of experience are accessing the totality of the past; and how neurology and the mind-brain interaction impacts human experience. This analysis leads to a lot of questions: Is the past constantly present, in that it is an active influencer on all our actions? When we relive a past event, where does that live in our minds vs. bodies? Are we tapping into a universal storehouse of past events, or are we tapping into past lives (or into others past lives)? When we sense that someone is looking at us, what is that?

He also discusses his realization that the experiential element of non-ordinary states of consciousness was the most important; his entry point into breathwork; why breathwork creates a perfect atmosphere for conversation; reincarnation and the idea of being reincarnated into other dimensions; the concept of objective immortality and how ripple effects from a single moment continue onward; and the fallacy of misplaced concreteness and psychoid experiences: Are they real beyond our psyche?

“One of the key moments for my studies was [when] I was tripping, walking through this room. Suddenly, I had this vision of three overlapping circles of psychology, philosophy, and religion, and in the middle was an experiential center that was all of them, where the experience of these questions and mysticism and psychological insight were sort of all flooding in there. And I thought: Wow, this is the insight people are talking about. I’ve got to find out what this is about.”

“Whitehead has a book called Religion in the Making and he says religious experience, a mystical experience is interesting and part of the picture, but you can’t build an entire religion or philosophy based on extraordinary experience of a few great men. But I think with psychedelics, opening up these realms to millions of people; it creates a much better foundation for doing something like that.”

“Everything’s alive, and I think we need to feel that again and to feel the depth dimensions that psychedelics reveal. …I think when we don’t feel the aliveness around us, we don’t feel alive.”

Psychedelics Today: PT316 – Lenny Gibson, Ph.D. – Vital Psychedelic Conversations

Psychedelics Today: John B. Cobb – Whitehead and Psychedelics

Parapsychology, Philosophy, and Spirituality: A Postmodern Exploration, by David Ray Griffin

Intensity: An Essay in Whiteheadian Ontology, by Judith a. Jones

Religion in the Making, by Alfred North Whitehead

Psychedelics Today: Psychedelics, Philosophy, Transhumanism and Peter Sjöstedt-H

Psychedelics Today: PT256 – Matthew D. Segall, Ph.D. – Consciousness, Capitalism, and Philosophy

Adventures of Ideas, by Alfred North Whitehead

Quantum Mechanics and the Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead, by Michael Epperson

In this episode, Joe interviews Dana Lerman, MD: a decade-long infectious disease consultant who has since been trained in psychedelic-assisted therapy, ecotherapy, and Internal Family Systems, and is the Co-Founder of Skylight Psychedelics, where she prescribes IM ketamine and trains therapists who work with it.

Lerman tells her story: how working with kids with cancer made her want to learn medicine, what it was like working as an infectious disease expert during COVID, and how fascinating it has been to start with modern medicine and then fully embrace the traditional frameworks of ayahuasca ceremonies. She has realized that part of her role is to bring that intention, ceremony, and inner healing intelligence to modern medicine – that that will greatly benefit patients as well as clinicians who naturally want to be healers but are burnt out by the bureaucracy and distractions of the faulty container they find themselves in. Skylight Psychedelics is working on opening a clinical research division, researching psychedelics for Long COVID, and bringing in-person psychedelic peer support services to emergency rooms.

She also discusses intergenerational trauma and how psychedelics have affected her parenting; the impossibility of informed consent in psychedelics and why there should be disclaimers as well as instructions; accessibility, the need for insurance to cover psychedelic-assisted therapy, and why the price of these expensive treatments actually makes sense; why we should be sharing stories of mistakes and things going wrong during ceremonies; and why one of the biggest things we can do to further the cause is to educate our children and parents about psychedelics.

“What’s come to me recently in ayahuasca ceremony is that part of my role in this space is really to bring intention and to bring ceremony and the inner healing intelligence and that concept to the modern medicine space. I mean, there’s so many places for improvement in modern medicine, like even: We have a few minutes for a timeout so you can check to make sure that’s the right patient [and] it’s the right limb you’re going to amputate, but we don’t have a moment to talk about who this person is and the intention of this surgery and what we want for this person. We just have this disconnect, and this disconnect; obviously, it’s not just in medicine. It’s in everywhere. It’s our food. It’s our community. All systems.”

“I have three small children. A lot of why I went to ayahuasca was because I knew [beside wanting] to heal myself of all the stuff that I’ve been carrying around, I wanted to shift my parenting and to be a better parent, and I felt that if I carried my anxiety, my control, all the stuff: It just keeps getting passed down because the kids are just learning from us. But if you can address that, if you can address where does that come from, what is the work that has to be done around it, and do that work, your kids see it. My daughter: When I came home from ayahuasca (she was probably seven); she looked to me and she said, ‘Why didn’t you go there sooner?’”

“Anytime people are using these medicines, I think: There’s a huge disclaimer that should be coming with these medicines, like: ‘Your life will be changed forever. You will never look at anything the same way again, and there’s a possibility that you enter into a space where you are experiencing the vastness of the universe, and that may be very overwhelming for you when the journey is over. You need someone to talk about it with.’ The whole concept of integration is so important.”

Vera.org: John Ehrlichman’s quote about the war on drugs

Uthscsa.edu: Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, MD

Apollo Neuro: Click here to get $50 off an Apollo wearable!

In this episode, Johanna interviews Jungian analyst-in-training, writer, researcher, 5Rhythms® teacher, and Vital graduate: Mackenzie Amara; and Vital instructor, clinical psychologist, and creator of our new course, “Illuminating the Hidden Self: Navigating the Jungian Shadow with Psychedelics“: Dr. Ido Cohen.

This sequel to their fascinating discussion about shadow work earlier this year focuses on dreams, as Amara, while dreaming that she was having an acid trip and coming to the realization that dreams and LSD may be sending her to the same place, is researching the similarities between the odd worlds of dreams and psychedelic experiences: Is it the same place? Do the dreams we have after psychedelic experiences continue those visions and ‘Aha!’ moments? Can they answer questions for us (the concept of “sleep on it”)? Does dream analysis result in a greater feeling of integration? Can we use the dreams we have before experiences to help guide the experience itself?

The conversation goes a lot of places: the many aspects of Jungian psychology; the fluidity of Indigenous perspectives around visible and invisible worlds; how Jung wrote “The Red Book”; the concept of eros and reclaiming our relationship with aliveness; how nature is in constant equilibrium (as are we); how to build a relationship with your dreams; how to work with symbols in dreams; and much more. Ultimately, this episode is about the clash between the conscious and unconscious, the willed and the incidental, and waking life and other realities, and dream analysis and integration work is really tracking vitality in the human psyche: what is alive in us and how does it want to live out in our beings? What makes us come alive? Can our dreams tell us?

“I was inside my dream, analyzing my dream, and having the phenomenological experience of being on LSD, and it was like, ‘Holy shit, is this the same place?’” -Mackenzie

“When you sit with a dream image that maybe scares you or that you avoid: When you sit with it long enough for its purpose to be revealed, it’s like, ‘Man, cool, thank you for sending me that image.’ And you can start to trust that there’s something larger inside of you that has your back. And that level of trust, that level of existential secure attachment (is what I’ve been calling it lately) is un-fuck-with-able. Nobody can take that from you. Once you have that, you’re good. All the chaos can happen around you, but you’ve got something inside of you that nobody can touch.” -Mackenzie

“These are all experiences with the numinous. The numinous wears all the shapes. It’s only our human hubris that searches for it in particular shapes. If we kind of quiet that hubris a little bit and let the self, let the numinous talk in its own language for a second, we can all be humbled to see how vast its language is and how it can find us even in the most ridiculous images.” -Ido

“When we have these experiences, when we’re given this content from our unconscious, it’s an invitation to join the family, to join the life that is living through all things. And that to me, is just really, really hopeful, and I think it’s why I’m so inspired and passionate about psychedelics, is the possibility of them to alleviate that nihilistic thought pattern that says ‘I’m alone in this world.’ When we really, really feel into what’s happening for us, it’s collective. We’re in a collective experience, constantly, all the time. And that’s really beautiful and healing.” -Mackenzie

PT390 – Vital Psychedelic Conversations, featuring: Mackenzie Amara & Dr. Ido Cohen

Illuminating the Hidden Self: Navigating the Jungian Shadow with Psychedelics

Kannaextract.com (Use code PT10 for 10% off!)

In this special episode, Melanie Pincus, Ph.D. and Manesh Girn, Ph.D., who joined David in episode 403 to discuss the launch of their new course, essentially interview each other.

As the 2nd edition of their popular course, Psychedelic Neuroscience Demystified, begins on November 1, we wanted to give them a chance to highlight some of the aspects of neuroscience students can expect to learn in the course, and what so many people who are interested in psychedelics don’t fully understand: What does neuroplasticity actually entail? Can one predict if a patient is more apt to have an experience with ego dissolution? How does the amygdala relate to mood disorders? When are critical periods of greater plasticity and socialization at their most beneficial? How does neuroplasticity relate to chronic stress?

They also discuss lessons they’ve received from their own journeys; why they created the course; serotonin; psychological flexibility; body-based versions of self vs. memory-based versions; psychedelics and re-encoding memories (and the potential for false memories); how psychedelic therapy is different from standard drug treatments; psychedelics and the default mode network (is the story oversimplified?), and much more.

For more information on their course, and to sign up, click here!

“A major insight from my psychedelic journeys is just how dense and heavy thoughts and mental content can be. And we often feel the need to overanalyze and think about things and get lost in our concepts and internal dialogue as opposed to experiencing things in the moment, as they are, in a more deeper kind of intimate way – having a greater intimate relationship with our senses, with the immediacy of what’s happening. And my psychedelic experiences, whether it’s with psilocybin or 5-MeO-DMT or what have you, have allowed me to glimpse into states where that stuff is just totally removed, and I’m just immersed in the rawness of experience and just how beautifully vibrant and alive and spontaneously intelligent that is, and how superfluous a lot of our thinking really is, and it just weighs us down. I think my journeys have just allowed me to live with greater ease and hold on to my identity and my narratives much more lightly. So I see them, I acknowledge them, but I’m not totally lost in them. I don’t identify strongly with them.” -Manesh

“Perhaps what’s happening is that MDMA induces a super positive mood where you feel really socially connected, really empathogenic with your therapist or whoever’s around you, you feel so safe and supported. And so if challenging traumatic memories come up, there’s this mismatch between the emotional trace of the traumatic memory and the unique state you’re in with the MDMA on board. And so this mismatch drives the memory reconsolidation process so that your traumatic memory is amended with less fear to be more in line with your current way you’re feeling of being so safe and supported.” -Melanie

Opening Critical Periods with Psychedelics, by Melanie Pincus, Ph.D. & Manesh Girn, Ph.D.(c)

PT258 – Manesh Girn – Psychedelics and the Brain: Neuroplasticity and Creativity

In this episode, Kyle interviews Rachel Harris, Ph.D.: Psychologist in private practice for over 40 years, researcher who has published more than 40 peer-reviewed studies, and author of the new book, Swimming in the Sacred: Wisdom from the Psychedelic Underground.

She talks about graduating college and going straight to Esalen, where she had little concern over therapy or integration, and how, after 20 years of ayahuasca experiences, she learned to see psychedelic-assisted therapy and ceremonial, transformational experiences as very different things. She discusses her ayahuasca journeys; a surprising MDMA experience; what having an ongoing relationship with the spirit of ayahuasca means; Ann Shulgin’s concerns over going through death’s door while in a journey; what true integration is; how psychedelics can help prepare for death, and more.

And she talks about her new book, Swimming in the Sacred, which collects the stories, unique perspectives, and wisdom of 15 female elders who have been working in the underground for at least 15 years each, and how their experience has led to a somatic-based intuition and ‘know it in their bones’ feeling that so many new practitioners and facilitators need – and can only come with time.

“I kind of want to say to the newly-hatched psychedelic therapists: ‘Well, get this experience,’ but it’s very hard. And they’re not going to wait six years before practicing, so there’s such a need for them, and I can’t, in every podcast, (I mean, you’ll laugh at this), I can’t say, ‘Go do a lot of drugs,’ right? I’m trying to be more elegant about this, but that’s part of the elder women’s experience, is they really know the territory.”

“I know you’ve done a real apprenticeship, and I really respect that. And, yes, it’s very hard to find them, but that is the way people learn. So, what’s the best way to become a psychedelic therapist? It’s to be a patient with someone who’s a very experienced psychedelic therapist.”

“My priority was to work on myself and to grow and evolve. And so I always think of integration as part of a whole life: it’s not something that happens in a couple of sessions. But after these experiences, then what do we do with our lives and how do we live a more integrated life? And how do our lives unfold?”

Buy Swimming in the Sacred on Amazon

Ayahuasca in My Blood: 25 Years of Medicine Dreaming, by Peter Gorman

The Secret Chief Revealed, by Myron J. Stolaroff

Pubmed: A study of ayahuasca use in North America

Lament of the Dead: Psychology After Jung’s Red Book, by James Hillman & Sonu Shamdasani

Eatfungies.com (Use code TODAY20 for 20% off at checkout)

New course starts October 10: Navigating Psychedelics: Jewish-Informed Perspectives on Psychedelics

In this episode, David interviews Dr. JoQueta Handy, Ph.D., IMD: speaker, author, educator, Natural Integrative Health Practitioner, and CEO and Chief Visionary of Brilliant Learning, Handy Wellness Center, and Brilliant Blends.

She shares childhood memories of growing up on her Grandparents’ farm, where she developed a deep appreciation for nature, staring at the stars, and the beauty in stillness, and how coming back to that stillness has been key in her life and psychedelic journeys. The conversation then shifts to all that she’s learned through her work with children on the autism spectrum: the problems of putting people into boxes; how autism affects everyone; the different ways people learn; the connection between autism and the gut microbiome; and how she has learned more from some of these children than any book could teach her – culminating in a story of discovering that a very challenged child people were ready to give up on could actually read and comprehend everything he was hearing.

She discusses her favorite adaptogens; the art of stacking adaptogens and different modalities; her multi-day coaching sessions; Internal Family Systems; quantum biofeedback; the use of supplements in microdosing; and Brilliant Blends, which sells blends of supplements designed to provide benefits as close to what psilocybin can provide (but legally) – inspired by the unique needs of autistic individuals. PT listeners can receive 10% off all purchases with code: PT10.

“If we look at Western medicine, we are masters at saving lives. We’re not so great at quality of life. And looking more toward Eastern medicine, European medicine: where body, mind and soul [is] more brought into play – healing, working on the mind, the emotional, the mind and the body for a complete healing… So that was really why I chose the path of natural integrative medicine because I did see that everything has a place. Everybody brings a talent to the table. …We, many times, need a village for healing.”

“I’ve had some wonderful mentors along the way, but being on the ground, so to speak – not just in a laboratory, formulating things – being hands-on with those children on a day-to-day basis: that was the greatest teacher of: how is this herb working? How is this adaptogen working? So when I went to formulate Brilliant Blends, I just knew it had to honor them because I was using that knowledge base. I use it on a daily basis with everyone. …Autistic children have taught us what we know from autism, and what we know from autism applies to everyone.”

“That’s the end game. That’s the bottom line in all of this work that we’re doing. That’s where the transformation and freedom is: to realize that this medicine is in all of us. Maybe we’re just using psychedelics to open that door to reveal it and show us the path how to anchor it, but this medicine is in all of us and always was. So if we can use these different pathways, these different approaches to lead us back home, then bravo.”

Mybrilliantblends.com (use code PT10 to receive 10% off all purchases)

Hemplucid.com (use code PSYCHEDELICS10 for 10% off all purchases)

In this episode, Kyle interviews Lisa Wessing: Clinical Psychologist and facilitator specializing in harm reduction at Kiyumí retreats in The Netherlands.

Wessing shares her personal journey and the shift from being uninspired with studying psychology to being a part of space-holding in Mexico and finding her true path. She dives into the world of Kiyumí retreats, discussing their holistic healing approach using psilocybin, somatic movement, dance expression, and other methods supporting their four pillars of embodiment, nature, mindfulness, and art. She discusses their more long-term program with Dr. Gabor Maté integrating his Compassionate Inquiry framework; their Equity Program, which offers partial or full funding for people who may not have the financial resources or who come from marginalized communities (e.g. BIPOC & Queer); and the importance of integration as a continuous process and checking in with people much later to build their “Kiyumíty.”

Much of this discussion covers the challenges of somatic psychology and facilitation in group containers: how most people are somatically illiterate and the challenging journey of becoming more somatic; what to do about someone laughing or singing in a group context; what moving into one’s body really means; and different ways of using art to integrate an experience.

As part of our Vital program, we are running a psilocybin retreat with Kiyumí from September 6-11, and we have some available spots left! If you like what you hear, you’ll be in The Netherlands in September, and want to have an amazing experience with us, click here for more info!

“Something really important is expression: self-expression and expression in community. So seeing and being seen is something also that we value. And that seeing and being seen can create awkwardness and strangeness, and it’s something that we really like to also go into, because once we break through that awkwardness, there’s so much potential of creativity amongst people.”